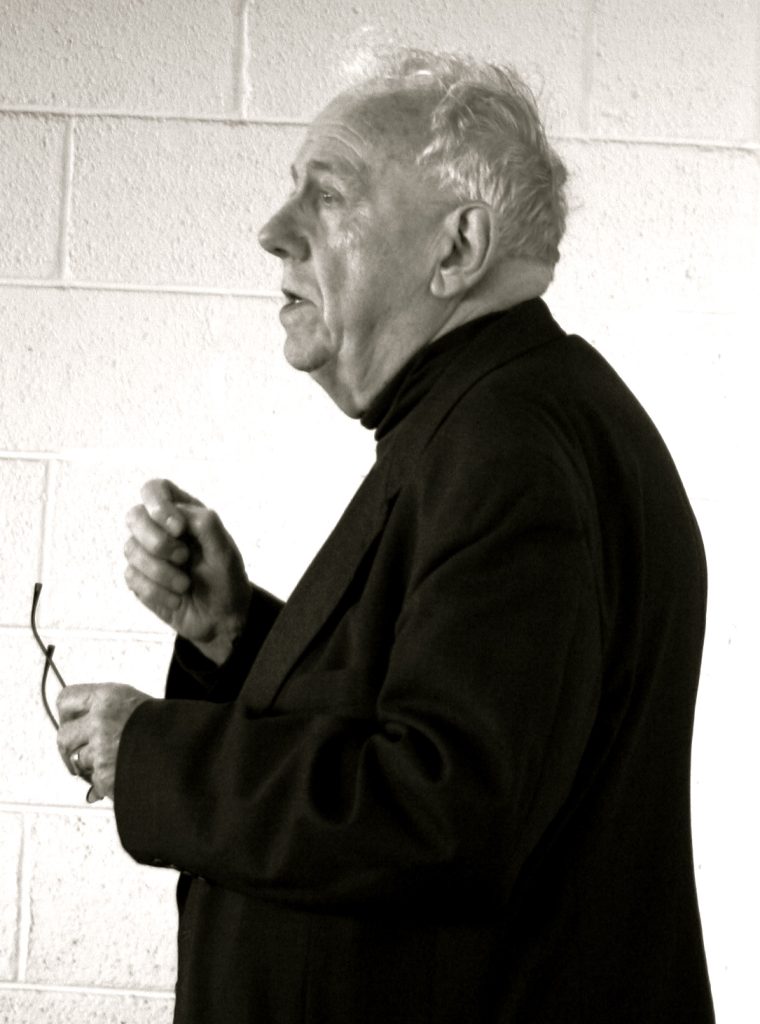

Quân Nguyen reflects on the teaching of Alasdair MacIntyre (1929-2025), an extraordinary philosopher whose criticism of liberalism should compel a withered Left to tend its own roots.

On 22nd May 2025, Alasdair MacIntyre died. The Glasgow-born philosopher who arguably was the most influential contemporary Scottish philosopher, who taught at countless institutions in Britain and the US, who embarked on a unique and remarkable intellectual journey, leaves behind a rich legacy and a central philosophical challenge for the Left.

Born in 1929, MacIntyre grew up steeped in Gaelic song and poetry, and after being disenchanted by the class contrast of Oxford elites and rural poverty, joined the Communist Party of Great Britain, only to leave in 1956, even before the Hungarian revolution would split it. He remained a Marxist for decades, with his publications focusing on Marxist thinking relating to Christianity, and he remained a scathing critic of liberalism and individual consumerism for the rest of his life. In Marx and Christianity (1968), he wrote:

Both liberals and Christians are too apt to forget that Marxism is the only systematic doctrine in the modern world that has been able to translate to any important degree the hopes men once expressed, and could not but express in religious terms, into the secular project of understanding societies and expressions of human possibility and history as a means of liberating the present from the burdens of the past, and so constructing the future. Liberalism by contrast simply abandons the virtue of hope. For liberals the future has become the present enlarged.

While already being disenchanted with the communist movement (he had ridiculed Stalinism long before for being a barbarous despotism, but treated it as irrelevant to the moral substance of Marxism in similar way that the Borgia pope was irrelevant to the substance of Christianity), MacIntyre turned away from Marxism in the 1980s, when he published his landmark book After Virtue (1981). In the book, he diagnoses Marxism as having become disoriented, unable to come up with their own intellectual contributions to any major development. Whether it was Soviet tanks crushing Hungarian workers, or Soviet leader Khrushchev’s crackdown on dissidents that sent shockwaves through the left at the time, Marxists would continuously revert to a form of consequentialism (the view that only consequences matter) or deontology (the view that there are moral rules not to be broken) to evaluate the events. Unable to tell its own story, Marxism suffered a crisis of faith that could not be mended easily.

However, the main aim of After Virtue, and what MacIntyre is remembered for, is an all-out attack on liberalism. According to MacIntyre, under liberalism our moral concepts have become devoid of meaning, lost to modernity, and we continue using words like “rights” or “justice” without them referring to anything meaningful. Liberals who debate morality and politics are like school children reading out the periodic table, or learning bits of the laws of thermodynamics by heart, a decade after all scientists were killed and scientific thought was systematically eradicated. The root cause of this loss of concepts is liberalism’s erosion of community where morality is practiced and exercised. Community gives meaning to morality. Without practice of morality within a community that recognises, knows and affirms moral agents, there can’t be meaningful morality, we just parrot whatever our ancestors have told us that morality is.

Outlining the threat of individual consumerism, liberalism and capitalist alienation for morality itself in Aristotelian terms of community and practice is what MacIntyre will be remembered for. Even when he later turned towards Christianity, he stuck by his anticapitalist critique, and embraced what he calls a “revolutionary Aristotelianism” of building robust and resilient communities that can outlast liberalism and where moral life can continue. “When asked in 1996 what values he retained from his Marxist days”, records The Nation, “MacIntyre answered, ‘I would still like to see every rich person hanged from the nearest lamp post.’” He presented a question for all Christians as to how so much of Christianity could have forgotten its radical potential, and challenged Christians to build a radical transformative Christendom that resists capitalism.

But MacIntyre also mounted a challenge to the left, here in Scotland and worldwide. Liberalism, as most of us will agree, is morally bankrupt, devoid of answers to the challenges of our time, and dying a slow death – but how does the left fare? Have we, like MacIntyre diagnosed for Marxism, lost our ability to come up with our own story? Are we morally disoriented, and lacking in community? Is the reason why left politics has been pushed to the fringes the lack of practice of our politics in our communities?

MacIntyre’s philosophy offers an explanation why the left has been on the backfoot, why our politics can’t develop traction, and why we have either to continuously refer back to old debates about leaders and writers long dead, or to accept the political terms of a dying liberalism. MacIntyre’s answer – a politics of the small community – is also worth criticising. The left needs a mass movement, a global and internationalist response to the rise of fascism across the world. Restricting our moral and political life to the small circle seems defeatist and insufficient. But MacIntyre is surely right that rebuilding the left cannot happen without firm roots.

Before MacIntyre came to embrace Christianity, he said that the Christian god is the only one whose existence is worth denying. For the Left in Scotland and beyond, he may be the most important philosopher worth disagreeing with.

Alasdair MacIntyre’s most important works:

- Marxism: An Interpretation (1953)

- A Short History of Ethics (1966)

- Marx and Christianity (1968)

- After Virtue (1981)

- Whose Justice? Which Rationality? (1988)

Quân Nguyen is a philosopher based in Edinburgh and Dublin.