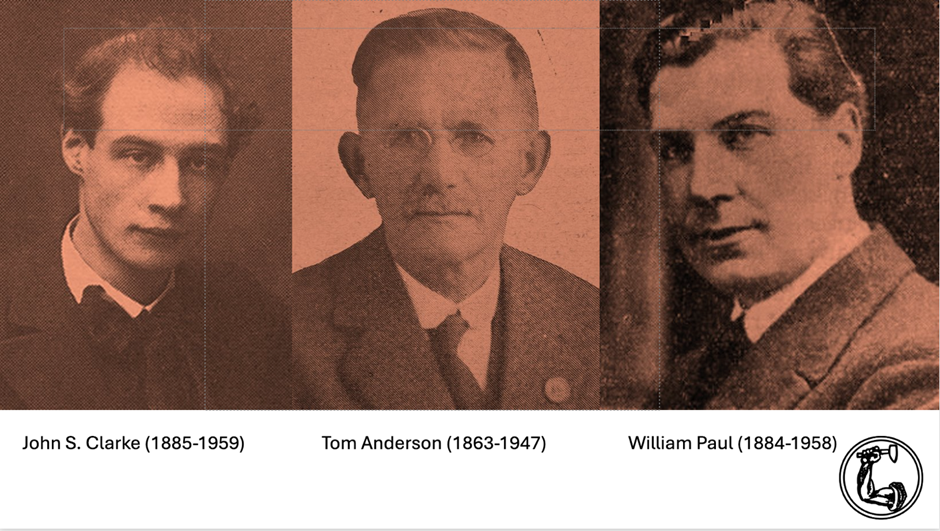

Tom Anderson, John Clarke, and Bill Paul were three Scottish Socialist Labour Party radicals who brought classical studies and stories into the language and learning. Henry Stead delves into the archives and documents their remarkable contribution to early 20th century Scottish socialism.

Tom Anderson (1863-1947) was the son of a handloom weaver in Pollokshaws, Glasgow. His biography is itself an education in the Scottish socialist revolutionary movement, passing as he did through various party affiliations including notably the Independent Labour Party, the Socialist Democratic Federation and latterly the Socialist Labour Party. He was a trade unionist and founder of the Socialist Sunday Schools, or Proletarian Schools, in Scotland. Given that he has not troubled the attention of the editors of neither the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography nor even the Dictionary of Labour Biography, he is perhaps best described by people who knew him. Two workers who set the type for his biography introduced him in 1930 like this:

“Old Tom, as we call him, was the first comrade in the world to teach the children of the slaves the meaning of Revolution. In 1894, he founded his first school.”

“When Tom had reached manhood, the problem which continually presented itself to him was the social condition of the people. He saw his class… the working class… existing in brutal poverty.

Why did the people who built grand mansions live in ugly, filthy and crowded slums; why did weavers of beautiful silks and rare velvets wear rags; why did the producers of food go hungry? These were some of the problems which confronted him.

He could not believe what the parson said, or his master or the foreman in the workshop. Why are the workers poor? Sin was the answer; but it was no answer for Tom. He read all the philosophers, but could find no answer.”

Anderson gave his own answer in his revolutionary magazines and cheaply printed and distributed books. Such literary activity demonstrates an energetic and wide-reaching intellect. A large part of his activism was dedicated to enlightening the proletarian youth, furnishing them with inspirational examples from history. But he saw the acquisition of culture, and especially its transformative social potential, as a counter-revolutionary force: Anderson believed that those workers who educated themselves in order to become great “men of culture” would ultimately “be of no use to the revolutionary working class movement.” “In fact,” he writes: “You will be one of its greatest opponents. [You will be] one who holds the safety valve on behalf of the master class, but an ounce of Revolution will not be in your being.”

So, how did Grecoroman antiquity figure in Anderson’s propaganda? Well, in Red Dawn, his magazine for Young Workers published between 1919 and 1920, he produced two important items in which he engaged with antiquity. The first is A Child’s Alphabet, offering a fairly perplexing roll-call of heroes of broad-church leftism from Abraham to Zeno, via Hannibal, Spartacus and Xenophon. Here figures from classical antiquity rub shoulders with heroes of the Labour Movement, Rationalists, two reformist Popes, Jesus Christ and several Marxists, including Anderson’s friend the communist poet Albert Young.

Quite as kaleidoscopic as his Child’s Alphabet, his ‘Across the Ages’ short stories did more or less the same thing, finding revolutionary exempla in an impressively global history, in which Greco-Roman antiquity is only one part. To give a sense of their content and style, I’ll zoom in on Anderson’s first story, which focused on the Syria-born ‘King of the Slaves’, Eunus. The main ancient source for the deeds of Eunus is Diodorus Siculus, but Anderson was not reading the Greek historian directly. He came across Eunus’s story in Cyrenus Osborne Ward’s Ancient Lowly (1887). In that influential prototype of much later ‘histories from below’, Osborne Ward remarked on how strange it was “that the great ten-years’ war of Eunus should be unknown”. After all, “he martialed at one time, an army of two hundred thousand soldiers. He manoeuvred them and fought for ten full years for liberty, defeating army after army of Rome. Why is the world ignorant of this fierce, epochal rebellion?”

Ward’s two-volume work was first published in 1887 in Chicago by Charles Kerr and Company. It was much read and frequently reprinted up until its plates were melted down for munitions in WWII. The Ancient Lowly was an unparalleled resource for the experience of the poor, the outcast, and the enslaved in Greco-Roman antiquity, and as such was frequently used by leftist writers. It was, for example, a key source for two novels about Spartacus. The first was by the Scottish writer Lewis Grassic Gibbon, whose Spartacus was published in 1933, and the second was by US communist novelist Howard Fast, whose self-published international best-seller was released in 1951.

Anderson’s telling of Eunus’ tale wastes no time before drawing parallels with the modern day, presenting Eunus as an ancient version of a labour organiser. He explains to his young readers that Rome, like Greece before her, was a slave state, citing the ratios of the enslaved population to free citizens that he found in Ward’s Ancient Lowly. He comments on parallels with the modern world, compering the violent British annexation of the South African Boer Republics to Roman imperialism in the second century BC. But he considered it “a travesty of truth” to draw parallels between modern socialist republics and “ancient Greece”, which, unlike the fledgling republics of the nascent Soviet Union, was “a slave state”. Such heavy and explicit emphasis on the fundamental exploitation of the enslaved mass in ancient Greek and Roman societies is unusual for this period, especially beyond the academy. But it was a prominent feature of 20th-century communist receptions of antiquity.

Anderson also equated the plight of Eunus’s formerly enslaved soldiers and that of the proletariat in early Soviet Russia. He parallels the cool confidence of Western international capital in the face of communist revolution with Rome’s capacity to crush the revolt by throwing more resources at it, year on year. The bloodthirstiness and cruelty of the Romans has been no preserve of leftist writers, but the comparison of capitalists with the Roman elite certainly is.

Osborne Ward’s book was not the only mediating source for leftist receptions of antiquity. Two other texts of huge influence were Lewis Henry Morgan’s Ancient Society (1877) and Engels’ Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), which reformulated Morgan’s anthropological findings to fit with Marx’s and Engels’ own conclusions about social evolution. Josef Stalin would later enshrine these conclusions in his chapter on historical materialism in the History of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, which was published in 1938 and translated into 66 languages before Stalin’s death in 1953. But before all that, radical workers were guided in their self-education by magazines like Anderson’s and by the affordable output of radical presses, including Kerr’s Chicago-based publishing company, which not only sold Osborne Ward’s Ancient Lowly, but also printed early English translations of Marx, Engels and an edition of Morgan’s Ancient Society.

Anderson’s short stories from history were reproduced in two slim and affordable volumes printed by Glasgow’s Proletarian Press in 1930 and 1932. The Welsh communist Islwyn AP Nicholas called Across the Ages “the most outstanding contribution to the literature of the Revolutionary Youth Movement in this country”, concluding that Anderson had “fired” the imagination of the working-class youth “with the ideal of Revolution” and taught them to “despise and scorn the hypocritical morality of Christian Capitalism”.

Anderson earlier monthly magazine, entitled The Revolution, had declared itself the ‘Official Organ of the Socialist School’. This publication ran from summer 1917 for around a year, and although Anderson did write a good deal of it under a handful of pseudonyms, other of its contributors shared his fascination with Greco-Roman antiquity.

John S. Clarke

John Clarke was born in Jarrow in 1885, one of fourteen children of an impoverished circus entertainer. A socialist poet, newspaper editor and author of books including Robert Burns and his Politics (1921) and Marxism and History (1938), the young Clarke also found employment in the fields of gun-running for Russian revolutionaries and lion taming. A member of the Independent Labour Party until 1932, he was one of very few to have given medical treatment to a dog belonging to Lenin, and perhaps the only one to have carried a box of snakes into the House of Commons. He met Lenin in 1920, when Scottish shop stewards elected him as their delegate to the Second Congress of the Communist International, but he objected to the Soviet cult of personality and never joined the CPGB.

Clarke supported Anderson’s revolutionary educational efforts by writing profiles of rebels from history. These would later be printed by the Proletarian School as The Young Worker’s Book of Rebels (1918), but they emerged first in Anderson’s Revolution. Clarke—who had a marginally better sense than Anderson of how to pitch his prose for younger readers— wrote on the second page of the first number of Revolution:

“A very great scientist named Karl Marx has told us that in order to understand human society we must study the “institutions” of society. By “institutions” he meant such things as Law, Property, Religion, Marriage, Militarism, etc. These “institutions” come into existence because they are likely to serve a useful purpose in man’s march of progress. Very often, however, an institution outgrows its usefulness, and when that happens it ceases to help the human race forward, and actually hinders its progress. Consequently that institution must be destroyed. Many people, though, do not wish to destroy it because it still benefits THEM. These are called conservative people or “reactionaries”.”

After arming his young readers with some useful revolutionary terms for the playground, Clarke continues:

“it has always happened in the past that a great struggle has taken place between those who wished to destroy the institution and those who wished to keep it. That is what is meant by “the class struggle”. Now, time has always proved that the destroyers were in the right, but it took them an awful long time to get the people to see it. The people had to be shocked or shaken into taking action. The men and women who did the shaking in the past and who do the shaking now are called REBELS. […]

It is my intention to tell you the stories of some of the world’s noblest rebels in order that you may remember them easily. I shall make each rebel the hero of a month in the year.’

In March 1918, the featured rebel was Spartacus. Clarke described the Romans Spartacus lived under as “the most wicked people on earth. Their amusements were revoltingly cruel, and they lived on the labour of ill-treated slaves. These slaves were mostly prisoners of war.” So here we meet our reactionaries and the social institution in need of destruction: slavery. All that was needed was a rebel leader to shake things up. Although he also took a lot of prisoners, Spartacus was not cruel and did not “injure a hair of their heads”. In a dig at one of his sources, the “rich man’s historian” Theodore Mommsen, Clarke emphasised that even this bourgeois conservative who “hated the idea of rebellion” had to admit that Spartacus was brave, strong and honourable. By calling Mommsen’s normative authority into question, Clarke both promotes direct action and provides a vocabulary of radical dissent.

Bill Paul

Our third radical antiquarian, Bill Paul, was born in Glasgow in 1884 but was politically active mainly in Derby. Like Anderson, he was a member of the Socialist Labour Party from its inception. But he was not such a convinced anti-Parliamentarian as Anderson, and had no compunction about joining the CPGB in 1920, quickly becoming the editor of the Party’s theoretical journal The Communist Review.

Paul wrote several books and pamphlets, including Hands off Russia (1919), Labour and Empire (1917) and Atomic Energy and Social Progress (1946). But he only focused squarely on antiquity in his 1917 book The State: Its Origins and Function, the contents of which he presented in abbreviated form for the young readers of Revolution. Building on the work of Lewis Morgan, Marx, Engels and Paul Lafargue, Paul wrote in social evolutionary terms about the passage from ‘Primitive communism’ to the ‘Rise of the State’, via the advent of private property, which, he explained, “smashed primitive communism” and replaced it with “a system with two classes struggling against each other – the master class and the working class.”

In a section called ‘The Rise of the State’, Paul notes the very same class struggle in the early civilization of Greece and Rome, which witnessed “a cruel and relentless struggle between the propertied and propertyless classes.” Without complicating his rigid binary system by commenting, for example, on manumission or the freed population, Paul states:

“In ancient Athens and Rome the State kept down the slaves; in feudal society it kept down the serfs in the country and the craftsmen in the towns; and in modern capitalism it coerces the wage-slaves. Its function has meant social intimidation for the enslaved throughout class society.”

It was common practice in contemporary SLP circles for workers to use terms of enslavement to refer to themselves as workers under capitalism, which is reflected in the slippage between the enslaved and the oppressed across all modes of production as presented here.

Taken as a group, these three radical socialists expounded in the clearest of terms the antiquity of ‘class struggle’, and the development of society from prehistory into the Greco-Roman world, using a theoretical framework adopted from Marx and Engels which became commonplace in the radical socialist tradition. Individually they spotlight a deep and enduring history of exploitation, stressing two key ideas which served to disrupt the status quo: A) that while it was extremely old, class division and the exploitation of labourers had not always gone unchallenged; indeed, as the early social formation of ‘primitive communism’ demonstrated, class society had not even always existed, and, B) that while their readers may have been educated to believe that the divisions of class and exploitation are natural and enduring, they were all in fact only a stone’s throw away from realising their own socialist republic. The red glow of ‘actually existing’ socialism that rose in the Soviet East was the final proof that things could and would soon be better. Theirs, then, was a confident and militant blend of left communism, according to which all roads led inexorably to a bright socialist future, and their ideas naturally found a firm footing in Red Clydeside.

Henry Stead is a Classical Reception scholar with a special interest in the reception of ancient Greek and Roman culture among the British working classes and the international left.